Quantum Physics Meets Experimental Filmmaking

Niccolò Bigagli, a sixth-year PhD candidate in physics, explains how he and filmmaker Ramey Newell created their award-winning short film.

The quantum world is weird. In it, matter is both a wave and a particle without a fixed position, unless it is observed. “Every time I read about quantum mechanics, my brain feels like it's exploding,” said filmmaker Ramey Newell. “It makes sense but at the same time, it doesn’t.”

Conveying the quirky, counterintuitive nature of quantum mechanics is a tricky challenge, but one that Newell recently took on alongside Columbia PhD student Niccolò Bigagli. The two paired up for this year’s Symbiosis Competition, sponsored by the Simon’s Foundation Science Sandbox initiative, to create a short film that would air at the 15th Annual Imagine Science Film festival.

Bigagli and Newell didn’t want to make any old lab explainer video. Instead, they wanted to create something abstract and a bit strange—“because quantum mechanics is rather abstract and strange,” said Newell. Their film—Interference Pattern—premiered on October 21, and the Symbiosis Competition jury awarded the pair first prize along with $1,500 for their attempt to capture the fundamental nature of reality. “Science and art are just two ways of exploring very similar questions,” said Ramey. “At its core, quantum mechanics is about trying to find the fundamental nature of reality. Filmmaking is the same; maybe not in such a physical or quantifiable way but very much in terms of our experience of reality.”

We caught up with Bigagli to discuss what went into making the film and what he works on here at Columbia.

How did you hear about the film festival in the first place?

Quite randomly. The Physics Department forwarded an email from the organizers about submitting a science pitch to an emerging science film festival that’s trying to rethink how science is portrayed, using film to develop more active engagement between scientists, artists, and the public. I thought that sounded fun and decided to apply.

Do you have any background in filmmaking?

An interest, sure. But knowledge? No. But the point of the competition is to pair scientists with filmmakers, so the scientists involved don’t need any prior experience. There were six of each of us: I represented quantum physics, but there was also an astrophysicist, neuroscientists, and biologists too. The filmmakers included animators, documentarians, and experimental filmmakers, including Ramey Newell, who I was paired with.

Can you explain the movie’s title, “Interference Pattern”?

The theme of the film festival and competition this year was “Science New Wave,” so we decided to play on the “wave” element, as waves are a big feature of physics, and of quantum mechanics in particular. There are matter waves, which I study and which we included pictures of in the film; light waves, which are the lasers we filmed in the lab and which provided the distinctive colors we see on screen; and sound waves. We actually wrote a function that will convert a color, or light frequency, into a sound frequency, so that when you are seeing a color on the screen, you are also hearing it. The higher the light frequency, the higher the pitch.

In physics, waves experience a phenomenon called interference—at its extremes, interferences can be either constructive, in which the waves add together and amplify each other, or destructive, where they cancel each other out. When you play pure tones, like our sound frequencies, in a theater, you can end up with both types of interference depending on where exactly you are sitting or if you are moving—that links to the observer-dependent nature of quantum mechanics.

That’s all reflected in our title: there’s the interference of different waves, and the constructive interference between physics and filmmaking of trying to make something bigger than the two disciplines by themselves.

What was the original idea behind your conception of the film?

I didn’t really have one. All I knew was that I wanted to make a film about quantum mechanics that was not just literally about the experiments we do in the lab. Since Ramey is an experimental filmmaker, we said, “let’s do something weird!” We wanted to convey these abstract notions of measurement and observer effects and the wave nature of matter, because that’s what quantum mechanics is all about.

We actually found a lot of parallels between quantum and filmmaking. For example, we both use light. Our lenses may look very different, but at the end of the day it’s all about using and shaping light waves, and how that can influence measurement and perceptions.

Can you walk us through the filmmaking process?

It had to be completed within a week, which, according to Ramey, is an intense schedule! Her short films can take months to film, edit, and produce. For this project, she used 16mm film, so that only gave us a couple of days to shoot in the lab before we had to send the film to be developed for editing.

As an experimental filmmaker, she’s very interested in the physicality of the film: What happens if you freeze it or burn it, or expose it to bacteria? So we just started experimenting. We exposed the film to different laser frequencies and played around with the different optical elements in the lab to see how that would distort and shape the images. All the effects you see are analog—even our initials at the end were etched onto the film with focused light.

Image Carousel with 4 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

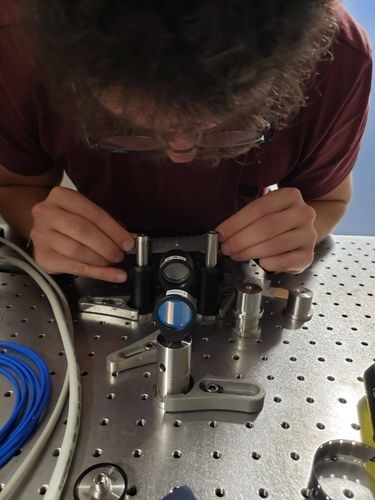

Slide 1: Columbia University PhD student Niccolo Bigagli adjusting an optical lens

-

Slide 2: Experimental filmmaker Ramey Newell filming gauges

-

Slide 3: Exposing the film to different laser frequencies

-

Slide 4: The 16mm camera in the lab.

Columbia University PhD student Niccolo Bigagli adjusting an optical lens

Experimental filmmaker Ramey Newell filming gauges

Exposing the film to different laser frequencies

The 16mm camera in the lab.

On top of that footage, we decided to take a trip down quantum memory lane with archival audio from scientists like Richard Feynman and Erwin Schroedinger. But as we noticed the parallels between our two fields, we decided to include quotes from filmmakers as well. It’s very interesting, if you don’t contextualize the quotes it’s almost indistinguishable whether they are talking about quantum mechanics or film.

We worried whether the film would be completely insane, but in the end, we felt something coherent came out of it.

As a scientist, what did you take away from this experience?

It’s very easy to get lost in the weeds day-to-day, and this experience was an opportunity to reflect on my science at a fundamental level, beyond “this is a hot topic in my field so let’s write an article about it.” Reaching out and getting conversations going outside of your discipline is very important.

Can you tell us about your research experience at Columbia so far?

I am currently studying atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) physics with Sebastian Will. We use ultra-cold atoms and molecules to explore quantum mechanics, which is a fascinating area. You can be very creative and do things that are not very intuitive.

I joined the lab just after Sebastian arrived at Columbia in 2016, so it’s been very exciting to help build a lab from scratch. There was nothing here, and now there are these machines that can produce these extremely cold, extremely weird objects and will outlast us all—well not Sebastian, but us graduate students.

For a while, we were just building and observing things that had already been done. It was, for example, extremely exciting when we observed our first atomic Bose-Einstein Condensate, a unique quantum state of matter in which individual particles start to behave as one unit, but that wasn’t necessarily something new. Now, though, we are starting to see things for the first time, things that we can’t even understand completely yet. It’s a very exciting time.

Any advice for others pursuing careers in physics?

A PhD is a very varied experience, and you will do a lot of things that you weren’t necessarily expecting at the beginning—like making a film! Try to welcome those opportunities as a positive. It’s fun to explore things from a different perspective, and important not to get too closed down in doing only one thing.