A Quantum Thesis Comes to Light

Leonard Kasday's PhD work on quantum entanglement, a subject that won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics, is now digitally available.

Last year, Columbia alumnus John Clauser won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on a quantum phenomenon known as entanglement, in which two particles remain connected to one another regardless of the distance between them. In a review article on the subject that Clauser wrote in 1978, he cites the work of Leonard Kasday, a contemporaneous Columbian who in 1972 completed his PhD thesis on the same topic. That document is a part of quantum history but, given quirks of US copyright law, existed as a single physical copy on the shelves of Butler Library. Now 51 years later, Kasday’s thesis has joined the digital era and is available online, thanks to the efforts of Columbia Physics professor Ana Asenjo-Garcia and Morgan Mitchell, a professor at the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Spain, where Asenjo-Garcia worked before joining Columbia.

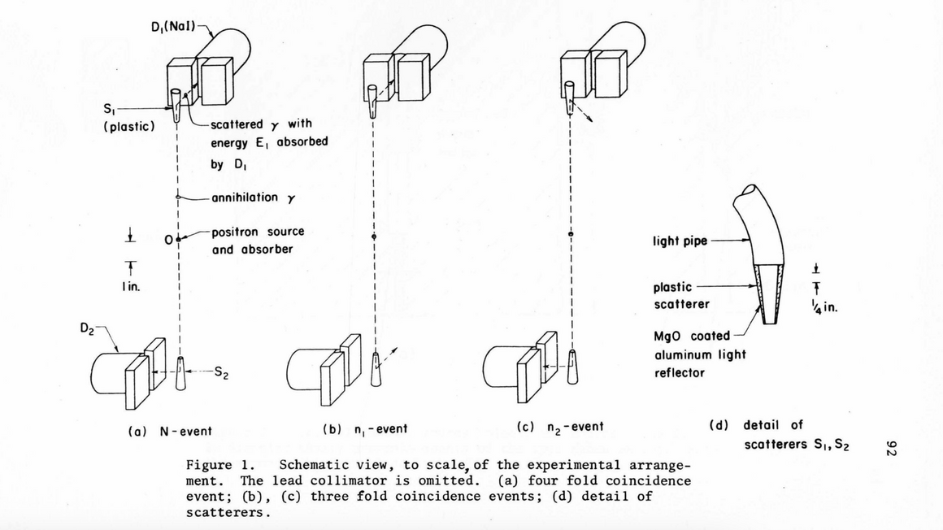

Kasday was supervised at Columbia by C. S. Wu, a physicist known for her work on the Manhattan Project who made foundational contributions to nuclear and particle physics. Kasday’s thesis centered on what are known as Bell tests, in reference to a theorem proven by physicist John Bell that first hinted at how entanglement might be experimentally observed. Kasday and Wu were close to proving the existence of quantum entanglement with Compton-scattered photon pairs from a positron-electron annihilation experiment, noted Asenjo-Garcia: “The pieces were all there, but the technology at the time was not.” Shortly after, Clauser and Stuart Freedman, a Berkeley PhD student, were able to conduct experiments demonstrating entanglement, which ultimately garnered Clauser last year’s Nobel.

Mitchell, who has collaborated on several Bell tests, knew of Kasday and Wu’s experiment from references to it in the literature. When the 2022 Nobel Prize was awarded, he resolved to study the original work, but, short of making a transatlantic trek to Columbia, there was no way to read it. He reached out to Asenjo-Garcia for help getting a copy.

Chapter by chapter, week by week, she requested scans from the Library. “Every few weeks, I’d receive a new chapter, and it was like a cliffhanger until the next one arrived,” she said. Three months passed before they had the complete thesis.

In a field that’s characterized today by preprints and open data, Asenjo-Garcia and Mitchell were eager to share the document, but they soon realized they couldn’t: Kasday never gave his permission for there to be a digital version.

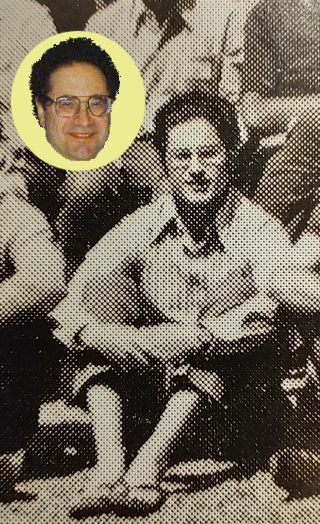

They began their search for the missing physicist. According to a now-defunct website, a Len Kasday had once worked at Temple University. But Temple’s Kasday worked on computer science—in particular, accessibility for those with disabilities. To Asenjo-Garcia and Mitchell, it seemed unlikely that it was the same person. Then, when preparing a colloquium on Bell tests, Mitchell came across a photo of Columbia’s Kasday from a 1970 conference in Varenna, Italy. They compared that photo to one on the Temple website and, to their excitement, the two Kasdays appeared to be one and the same.

Leonard Kasday graduated with his PhD in Physics from Columbia University in 1972. He continued working in physics, including spending a year working in a salt mine under Lake Erie to study a process called double beta decay.

His interests then shifted from physics to psychology. He obtained an NIH fellowship in experimental psychology at Columbia and New York University to study visual perception. During his fellowship, he developed a device that simulated, for people with normal vision, optical field defects like those experienced by some people with low vision. This device could be used to test accommodation methods in a controlled manner.

Kasday began working at AT&T Bell Labs in 1977 on a number of projects, including work on several assistive technologies, telephony, and optical tactile sensors. In 1998, he retired from Bell Labs and joined the Institute on Disabilities at Temple University, where he continued to promote and develop accessibility tools for people with disabilities until he passed away just two years later at 58.

But they had found Kasday too late; he had passed away in 2000, and the copyright to his thesis had passed on to his wife. But in another stroke of sleuthing serendipity, they found her: Linda Knight, Professor Emerita of Radiology at Temple University School of Medicine, and more than willing to check the box authorizing the release of her late husband’s contributions to Nobel-worthy quantum science to the wider world.

“With the Nobel Prize in 2022 being awarded for Bell tests, historians as well as scientists are interested in the pioneers of this field,” said Mitchell. “Kasday and Wu, along with Jeffrey Ullman, were the first to publish an experimental result on this topic (in the Varenna and other conference proceedings). That experiment and its contemporary interpretation are described in full detail in Kasday’s thesis. It is an important document, and we applaud the Butler Library for making it readily accessible.”