Information in computers is transmitted through semiconductors by the movement of electrons and stored in the direction of the electron spin in magnetic materials. To shrink devices while improving their performance—a goal of an emerging field called spin-electronics (“spintronics”)—researchers are searching for unique materials that combine both quantum properties. Writing in Nature Materials, a team of chemists and physicists at Columbia finds a strong link between electron transport and magnetism in a material called chromium sulfide bromide (CrSBr).

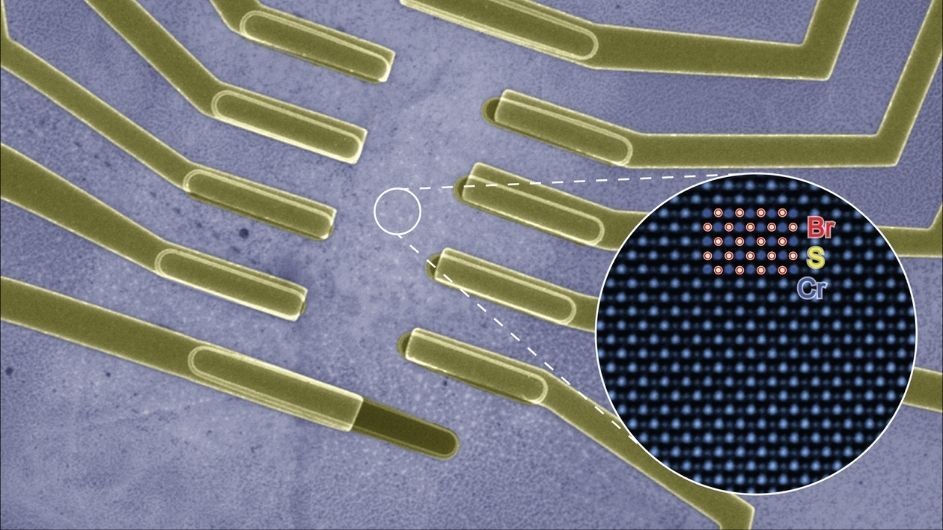

Created in the lab of Chemist Xavier Roy, CrSBr is a so-called van der Waals crystal that can be peeled into stackable, 2D layers that are just a few atoms thin. Unlike related materials that are quickly destroyed by oxygen and water, CrSBr crystals are stable at ambient conditions. These crystals also maintain their magnetic properties at the relatively high temperature of -280F, avoiding the need for expensive liquid helium cooled to a temperature of -450F.

“CrSBr is infinitely easier to work with than other 2D magnets, which lets us fabricate novel devices and test their properties,” said Evan Telford, a postdoc in the Roy lab who graduated with a PhD in physics from Columbia in 2020. Last year, colleagues Nathan Wilson and Xiaodong Xu at the University of Washington and Xiaoyang Zhu at Columbia found a link between magnetism and how CrSBr responds to light. In the current work, Telford led the effort to explore its electronic properties.

The team used an electric field to study CrSBr layers across different electron densities, magnetic fields, and temperatures—different parameters that can be adjusted to produce different effects in a material. As electronic properties in CrSBr changed, so did its magnetism.

“Semiconductors have tunable electronic properties. Magnets have tunable spin configurations. In CrSBr, these two knobs are combined,” said Roy. “That makes CrSBr attractive for both fundamental research and for potential spintronics application.”

Magnetism is a difficult property to measure directly, particularly as the size of the material shrinks, explained Telford, but it’s easy to measure how electrons move with a parameter called resistance. In CrSBr, resistance can serve as a proxy for otherwise unobservable magnetic states. “That’s very powerful,” said Roy, especially as researchers look to one day build chips out of such 2D magnets, which could be used for quantum computing and to store massive amounts of data in a small space.